10 Proven Writing Techniques that Work Great in 2024

Today you are going to see the exact ten writing techniques I use in every article I write.

These are the same writing methods I use to write for sites like Foundr, TheNextWeb, Entrepreneur, and many others.

What’s more, these types of writing techniques and strategies will help you boost your writing style and quality. You’ll only need to plug and play them in your next article, and you are done.

Let’s get started.

When you write, you want your readers to feel as if you are writing just for them. How do you do it?

There is a simple writing technique copywriters have developed to take the exact same words their readers use: review mining.

The idea behind review mining is simple:

Let’s say you were writing an article about car repairs, but you know nothing about the subject. What do you do?

If you start winging it, your reader will know it. It will be subtle, but it’s easy to see by someone who knows about the subject. It’s the same as when your father tries to “be cool” and talk like a young man.

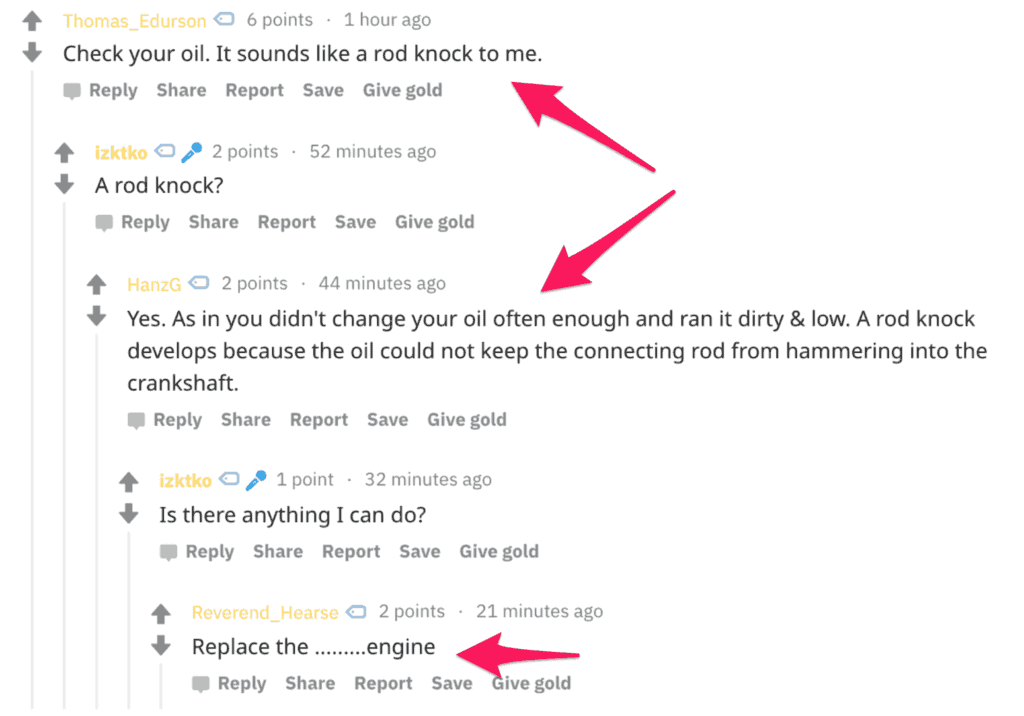

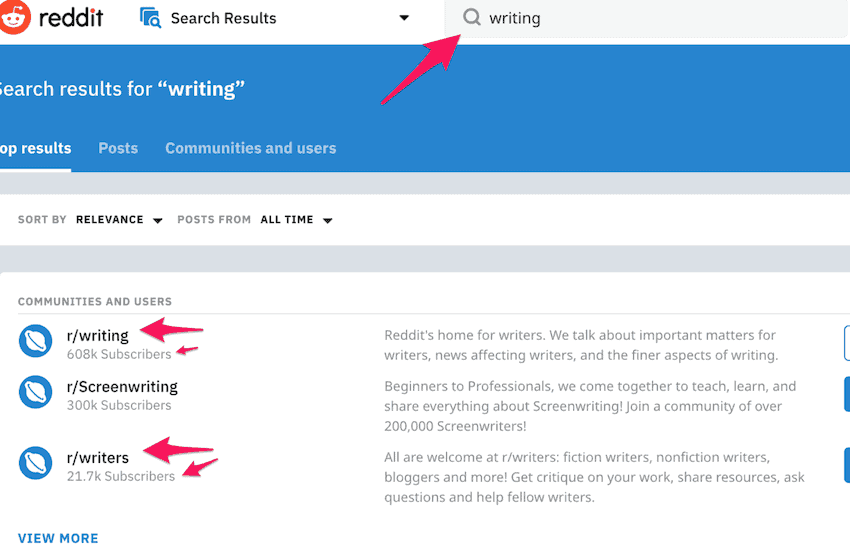

Instead, you go to a place like a Reddit, check the appropriate subreddit (like this one), and start reading through all the posts.

Slowly, you’ll start to pick up some expressions, slang, and mannerisms only people who repair cars use.

Here’s how you can review mine in your industry or niche.

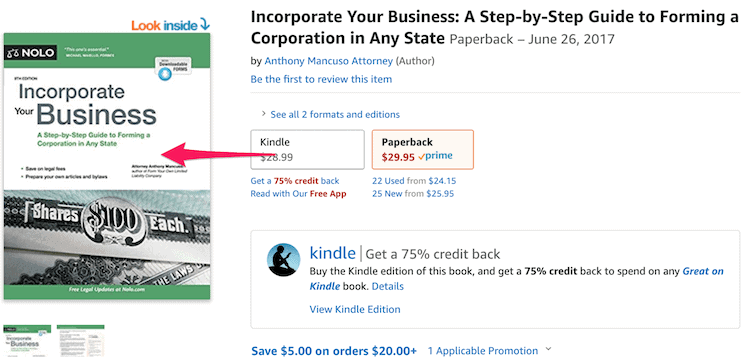

In Amazon’s search bar, add a broad keyword related to your content.

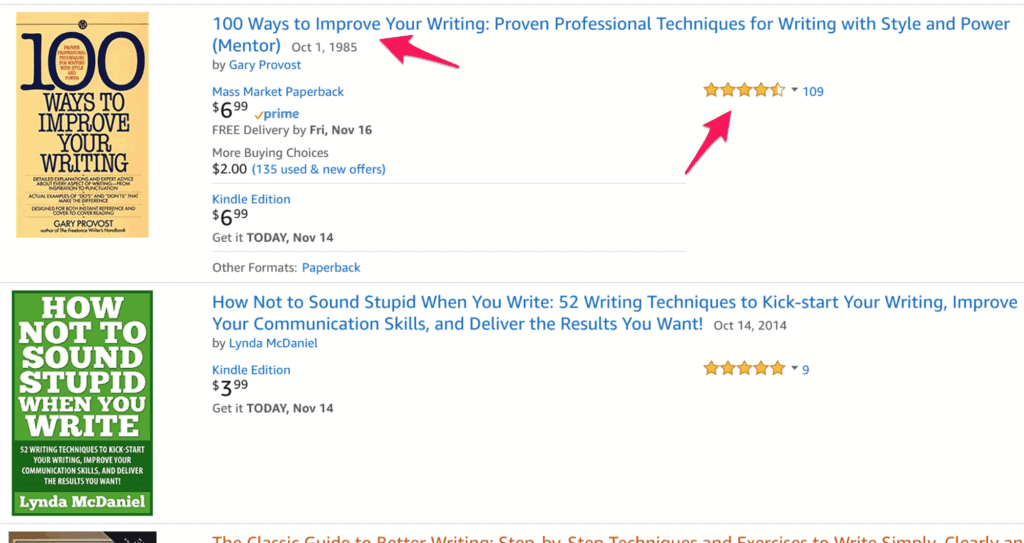

Then, scroll down and check the products that show up in the results. Open any result that has at least 50 reviews, like this book.

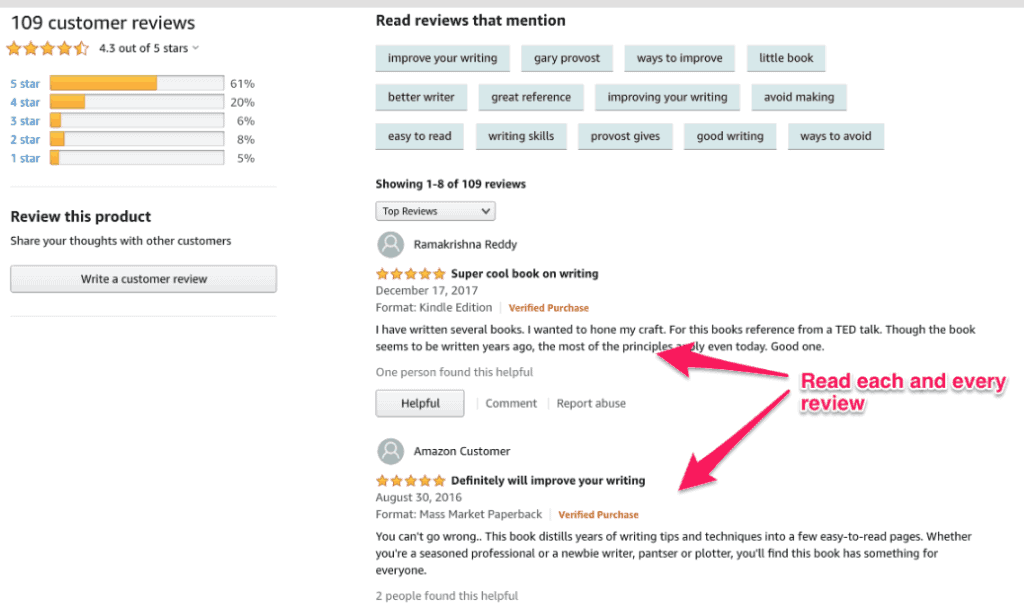

Go to the review section at the bottom of the page, and start reading the reviews one by one.

Open your favorite note-taking app—in my case, it’s Apple’s standard note app and Evernote—and copy each sentence, phrase, or word that seems unique or interesting.

For example, the expression “hone my craft” shown in the review from the image above seems like something that I could use in my content.

I also liked the second review, which says: “Whether you are a seasoned professional or a newbie writer, pantser or plotter, you’ll find this book has something for everyone.”

I could use an expression like that in a future article (I even considered using it for the intro of this guide).

Repeat that for every review in every product you find, books or otherwise.

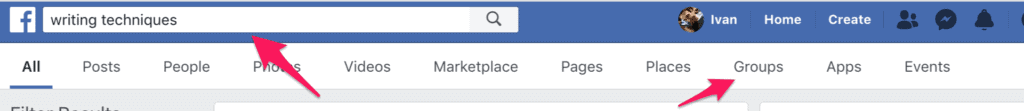

Go to Facebook and enter the same keyword in the search bar. Then, click on the “Groups” tab in the right.

Find a group that has at least 1,000 members. In this case, there seems to be only one group that fits that criteria.

Most likely, the group will be closed for non-members, so ask to join the group.

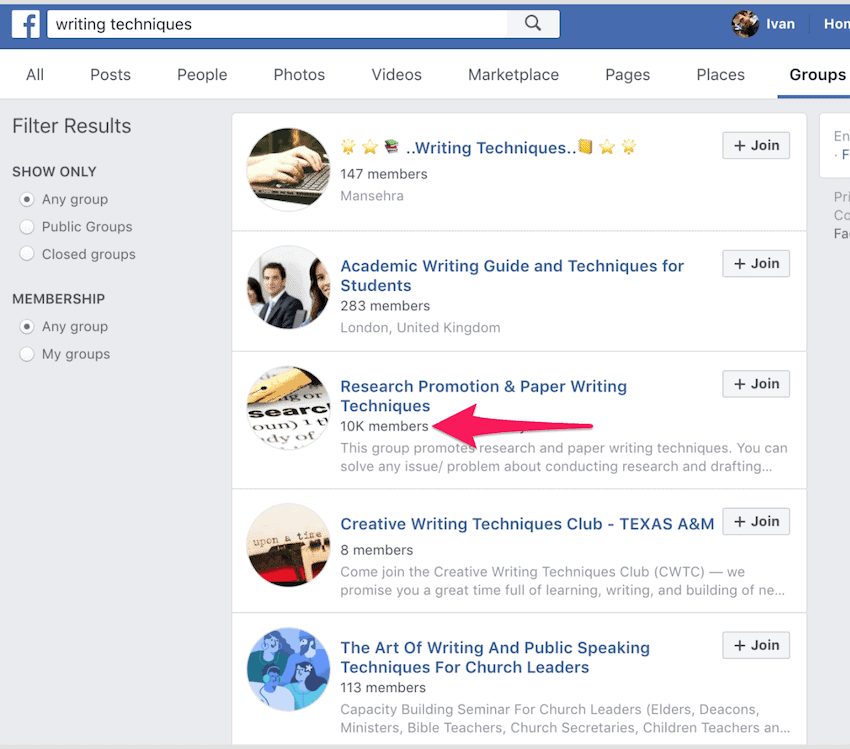

Once you’re accepted, check for posts with lots of likes, shares, and, most importantly, comments.

The post from the image above is an excellent example with some interesting expressions.

What’s more, it gives me the validation to write an article about what to do when a client changes your content. Some of the answers could be the same ones the people shared there.

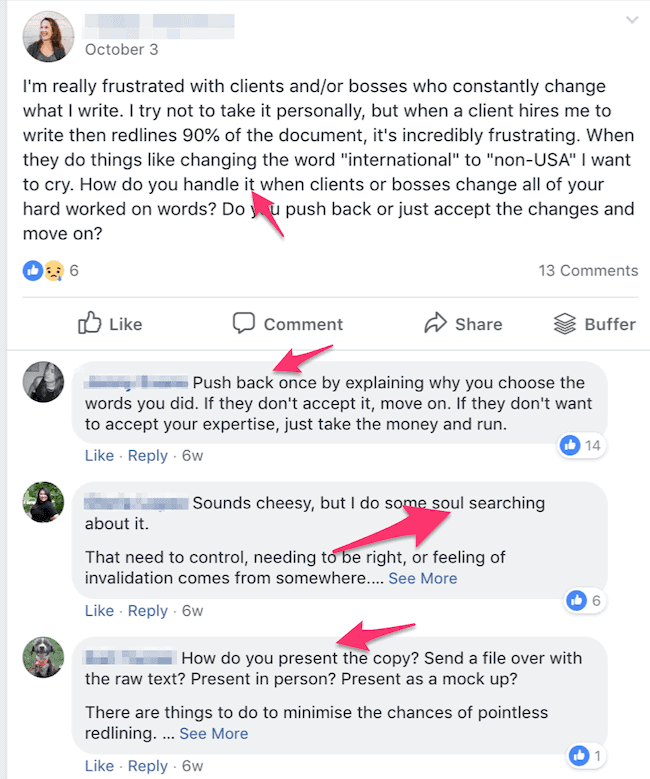

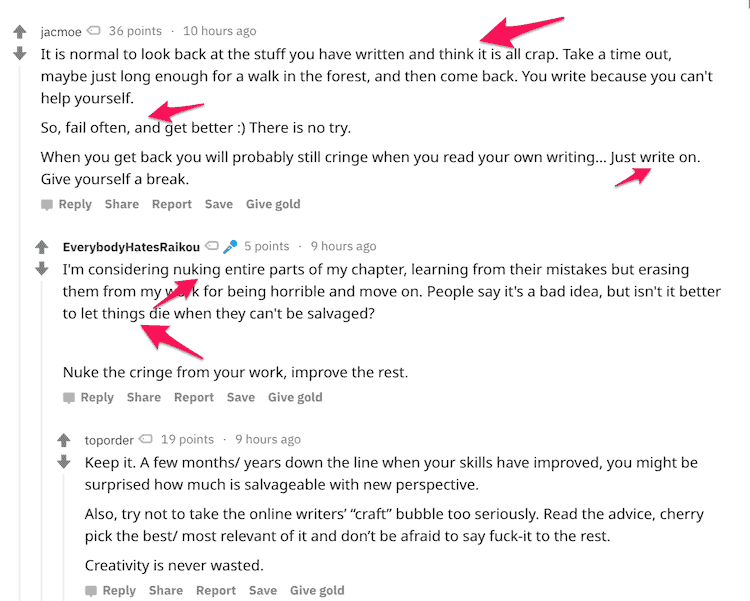

Go to Reddit’s homepage and look for a relevant subreddit.

Then, check the posts with the most comments.

One that caught my eye is one about quitting writing. Once I go to the post, I start reading the words from the OP (Original Poster) and the Redditors in the comment section.

The first sentence already looks like a fantastic intro. The rest is also pure gold, especially the expressions “just write on,” “fail often and get better,” and “nuke the cringe from your work, improve the rest.“

These peeps are a bit dramatic in their wordings, but what can you expect from writers?

The rest of the comments are as good as this one, which can help me figure out the common problems writers face and the expressions they use.

You can continue to repeat this same process anywhere where there’s a community, which includes:

To summarize, here’s how the review mining process works:

With review mining, your content will look relatable, honest, and clear. Your readers will feel like you are one of them, even though you aren’t.

Pretty cool, right?

Clarity is everything to writers.

When you write about a topic you understand, you know the exact ideas to express and their order of importance. But when you don’t, you get lost in the details. Worse yet, you may pick the wrong topics to start with.

What do you do? You could ask an expert. But a much easier way is to go where experts already are and see what they consider essential.

I’m talking about Wikipedia mining.

Wikipedia is the ultimate place where experts from all over the world gather to organize and explain different topics.

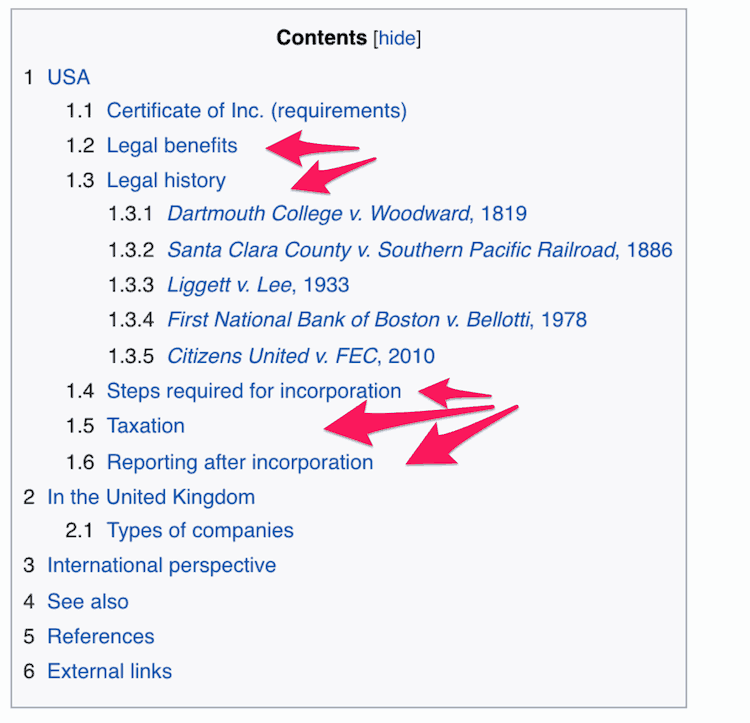

With Wikipedia mining, you look at a topic’s table of contents to determine how experts have structured the most critical points of a given topic.

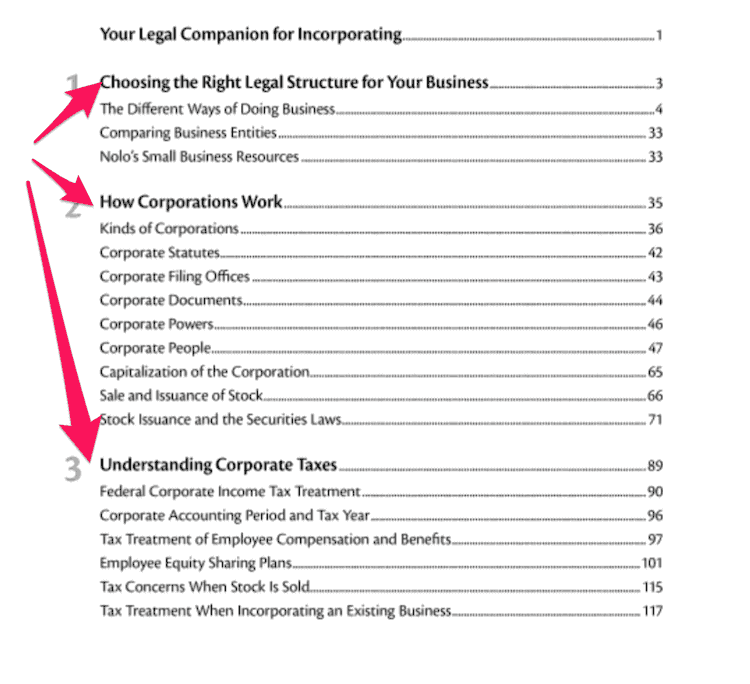

For example, let’s say you were writing about incorporating a business, a topic about which you are clueless. With Wikipedia mining, you’d to its Wikipedia page and see what you find.

Right away, you see the most important topics of business incorporation and how they could look in your article.

In a few minutes, you already have a basic structure of a complex topic.

The point isn’t to base a whole article or essay from Wikipedia; instead, it’s to use it as a guide towards a topic; as a starting point, if you will.

If Wikipedia doesn’t convince you, you can repeat the process with a book’s table of content.

A book—particularly a technical one—does a similar job as Wikipedia. Instead of reading a whole book, however, you use its table of contents to find the foundational ideas and their order.

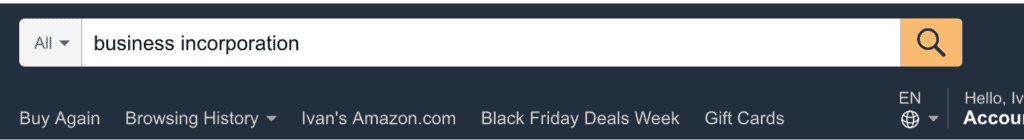

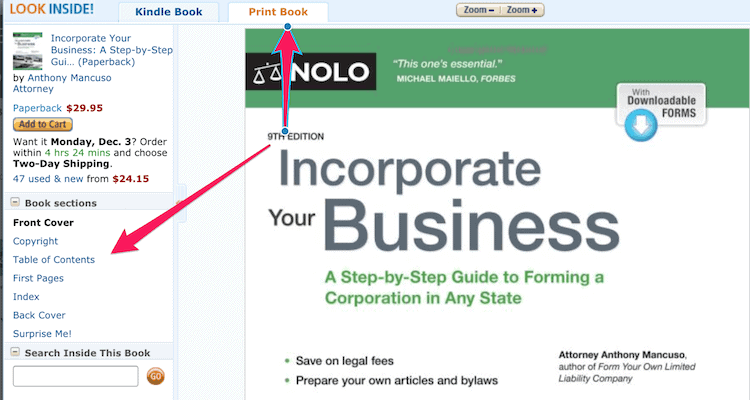

Following the business incorporation example, let’s go to Amazon and search for “business incorporation.”

Then, let’s open the first few books that seem relevant.

The “For Dummies” books are fantastic to learn new topics fast and discover the topics that matter.

Once on the product page, we’ll click on the book’s cover.

Then, we’ll select the print version (they’re more organized than the Kindle ones) and click on the “Table of Content” button.

Once in there, start reading everything in the table of contents, taking notes of the most important parts.

After you have repeated this process with a few more books, you’ll have a much clearer idea of the topics to write about and their order of importance.

Next time you are don’t know how to start an article, check Wikipedia and table of contents for guidance.

The proof is in the pudding.

You can act as an authority and give recommendations, action steps, and advice, but if you don’t show any proof of what you are saying, it doesn’t matter.

This reminds me of the scene of the movie Jerry Maguire when Jerry Maguire (played by Tom Cruise) starts screaming:

If you haven’t seen the movie, the scene’s background goes as following (spoiler alert!):

Jerry is a sports agent trying to convince one of his football superstar clients, Rod Tidwell (played by Cuba Gooding Jr.), to continue working with him after he’s fired for trying to be a more honest agent. To convince Rod, Jerry needs to prove himself.

That’s why instead of believing Jerry’s words, Rod asks him to prove his commitment by screaming, “Show me the money!“

What does this all have to do with writing? A lot.

When you write your content, you need to show your readers the money. In this context, “the money” means:

You must show any specific piece of information that takes your ideas from abstract…to concrete.

Copywriters have been using this writing technique for ages. They know they must make their copy believable, and instead of fighting with rational ideas, they simply show facts and numbers.

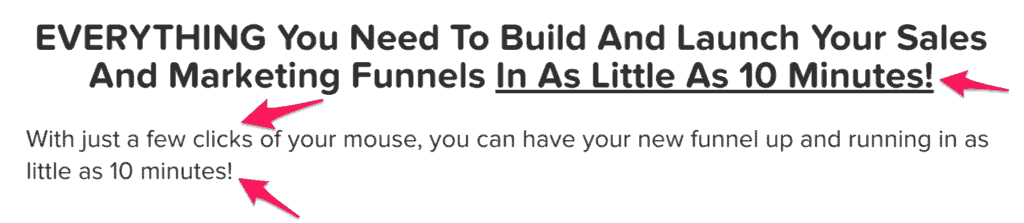

Take a look at the copy ClickFunnels:

You don’t build a funnel just “fast;” you build it in under 10 minutes. Simple and concrete.

Take a look at this example:

Why do you think a blogger like John Lee Dumas is so popular in the affiliate marketing niche? Because everything he says goes next to the proof of the results of his actions: the monthly six figures he rakes from his blog and other businesses.

The same applies to any article where you want to give advice. Sumo writers (like the great Chris Von Wilpert) know to have their advice stand out in the marketing industry is to show results.

Sure, ecommerce stores should use discounts, anyone knows that. But if you see BlendJet generated $163,633,50 in 30 days from using such tactic, then you go from knowing to understanding.

It’s all about the outcomes—the proof where the money is.

Let’s use a real example. Imagine you were writing an article for a personal finance blog where you had to explain how using saving accounts from online banks can help people save more money thanks to their more generous interest rates.

You could say that alone, and it could be considered “good” by many writers. Add a link to the bank and let the reader do the rest.

Instead of doing so, do the math in front of them and show them exactly how much extra money they could make (i.e., save) by putting their money in an online bank instead of a traditional one.

Here’s how the piece of content would look like:

If you are looking to 10x your savings, Ally has some of the country’s best rates. With an annual yield rate of 2%, Ally gives you 65% more per dollar saved, comparing it with Bank of America’s meager 0.03% rate.

That means, if you put aside $100 per month, Ally would save you a net of $1,303.48. Bank of America, in sad contrast, would net you only $18.47.

In other words, Ally would make you $1,285 more for the same monthly deposit and time frame.

You can see leveraging online bank savings is a no-brainer, so you should open an account with them.

You have the responsibility of being truthful to your readers.

To make your content more specific and powerful, use specific numbers, dollar signs, percentages, and anything that can show your words’ results or outcomes.

Whenever you write, think as if your readers are thinking, “why should I care?” in every sentence and paragraph they read.

Your content needs to beam with authority and impact, so they can’t ignore your content even if they tried.

To do so, you must leverage social proof.

Here’s how Robert Cialdini, the mastermind behind Influence, defines it:

The principle of social proof states that one means we use to determine what is correct is to find out what other people think is correct. The principle applies especially to the way we decide what constitutes correct behavior. We view a behavior as more correct in a given situation to the degree that we see others performing it.

(See what I did there? That’s social proof.

With social proof, you are not just saying something out of thin air; you show authoritative people say so.

There are three types of social proof you can use:

Take a look at my articles; there’s almost no article I don’t write where I don’t use these three elements simultaneously. Except for stats, in this article, you can see multiple examples and quotes. Both say, “Ivan doesn’t believe this alone, all these other people (or cases) prove him right.”

For example, when I wrote this big-ass article about ecommerce growth hacking, I mentioned two statistics, one quote, and 19 examples.

Check any of my other previously written articles, and you’ll see the same pattern: stats, quotes, and examples are abundant.

It’s a PITA to find them, but I know that’s what makes my content much better than my competition.

So you have to explain a complicated, technical concept. What do you do?

Easy: compare it with something your audience knows.

A key phrase you can use to start a comparison is “it’s like X but for Y.” For example:

To give you an often-used example from the tech startup world. Nowadays, everyone is creating the next “Uber for X,” a process that the media has called it the “Uberification” or “Uberization” of the economy.

The reason the “Uber for X” popularity is it makes new innovative concepts easy to understand. Take a look at the following (bizarre) example:

Everyone knows what Uber is and the way it works.

Everyone knows weed.

You mix the two, and you get the “Uber for Weed.”

There are many more examples of “Uber-like” business, including:

The “X for Y” phrase is the easiest application of the “Compare and Conquer” writing technique for the simple reason it takes two ideas you know and creates a separate concept that’s easy to grasp.

This phrase, however, is only one way you can compare and conquer.

Roy Peter Clark, author of Help! for Writers, recommends other writing techniques to make your complex technical concepts easier to understand, including:

Compare and conquer. Make your ideas simpler by comparing them with something most get, and you’ll have a much easier time explaining technical concepts.

People have a short attention span. It’s not that they’re incapable of reading long text; it’s just that there are too many distractions vying for their attention.

Instead of giving an intro worthy of a college essay, start with what you will give away. Spill the beans in front of them.

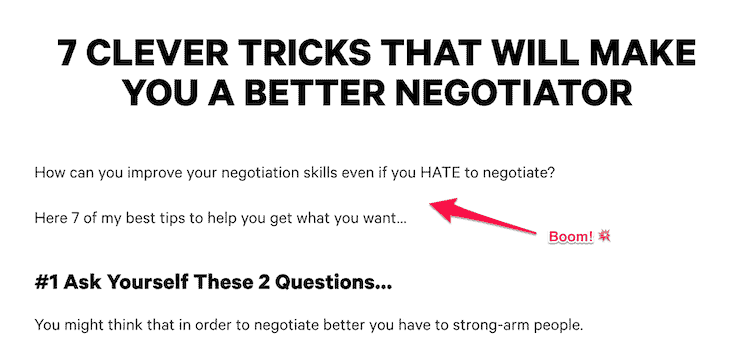

Take a look at what Derek Halpern from Social Triggers does in this post:

It doesn’t get any shorter than that.

Remember, people visit your content already knowing what’s it about thanks to its title. (An excellent reason to have a good title, which I will explain later.)

Since they have some idea of your content, start with that pre-existing knowledge and build the intro from there.

In the case of Derek from above, he follows a three-step formula:

Copywriters have historically developed a set of frameworks that helps them develop their copy structure, always focused on catching the readers’ attention and holding it long enough, so they read the entire copy, thus increasing the chances of converting.

One of the most common frameworks they used is called “PAS,” which stands for:

There are many more frameworks, but the critical aspect of such a structure is the same:

You can change your problem for a story, an anecdote, a fact, or anything that shocks the reader. What matters is that you build interest before starting to explain the hypothesis of your article.

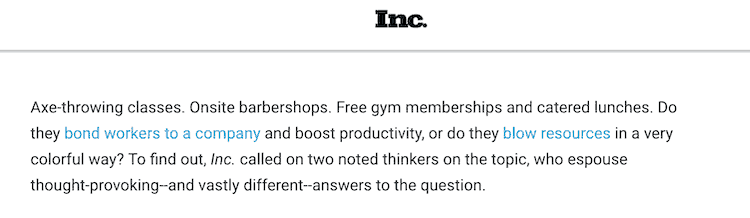

Inc’s writers always do a great job at creating short, catchy intros:

While this example doesn’t use a problem-agitation structure, they catch your attention by starting with short, seemingly random sentences, all of which tie to the idea of activities that bond employers together.

Similarly, Stefanie Flaxman from Copyblogger creates interest in her topic by tying the article’s topic with a personal anecdote:

While it’s not as concrete as Derek’s intro, it’s still short and concise. She even finishes giving a glimpse into the solution.

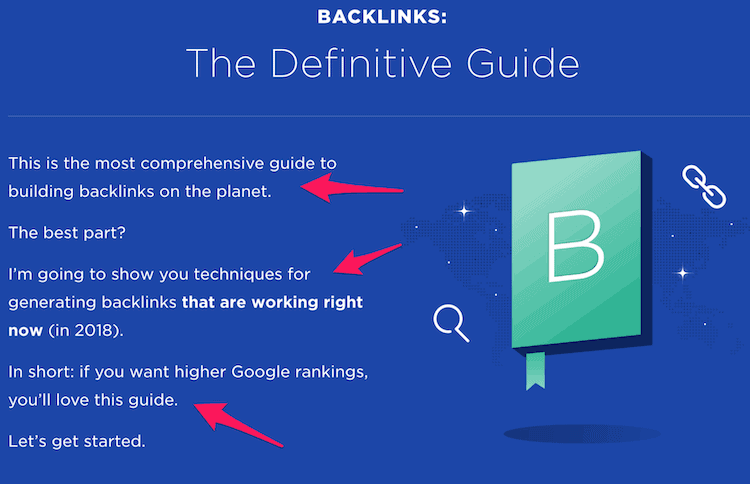

If there’s one writer I believe is the king of short, catchy intros is Brian Dean from Backlinko, who spares no time to create a lot of interest in his articles:

One of the subtle aspects behind every average writer is that their content looks “flat.”

That is, when they describe an idea, they do it without playing with the “dimensions” of your imagination. Those dimensions are your senses.

As you know, there are five senses:

When you engage the senses, you add a layer of complexity to your content; like the subtle flavors of a fancy coffee or wine, it lets your readers enjoy your content in a way they’ll have a hard time explaining.

They will simply like it without being able to point out what it is they want. You’ll know what it is, I’ll know what it is, but we’ll keep that as our secret, shall we?

When you write, you can tap into each one to add “flavor” to your content using specific words that connect them with a specific sense.

Newton is considered the greatest physicist ever to walk on Earth.

Whatever the case, Newton was also a pretty humble man. When he wrote to a friend of his about his jaw-dropping discoveries, he said: “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.”

Borrowing the idea from his humble quote, I call this the “Newton principle“: when you write, stand on the shoulder of giants.

Check what other people successful writers have done and copy them.

The act of copying your idols, heroes, and favorite artists will help you learn from the best of your craft. You will learn by association; the closer you are to them, the more you will take.

For example, I love to read because it teaches me to write. Stephen King explains this point in On Writing (emphasis mine):

Every book you pick up has its own lesson or lessons, and quite often, the bad books have more to teach than the good ones.

Good writing, on the other hand, teaches the learning writer about style, graceful narration, plot development, the creation of believable characters, and truth-telling.

Reading is the creative center of a writer’s life.

The point isn’t to take the exact words of my heroes and changing them for mine. As King explains, the goal is to learn how they express themselves and the tools they use so I can use them when I write.

Then, I adapt their writing techniques and change them to match my own ideas and expressive methods. It’s a subtle task, but it’s imperative to learn to become better at your craft.

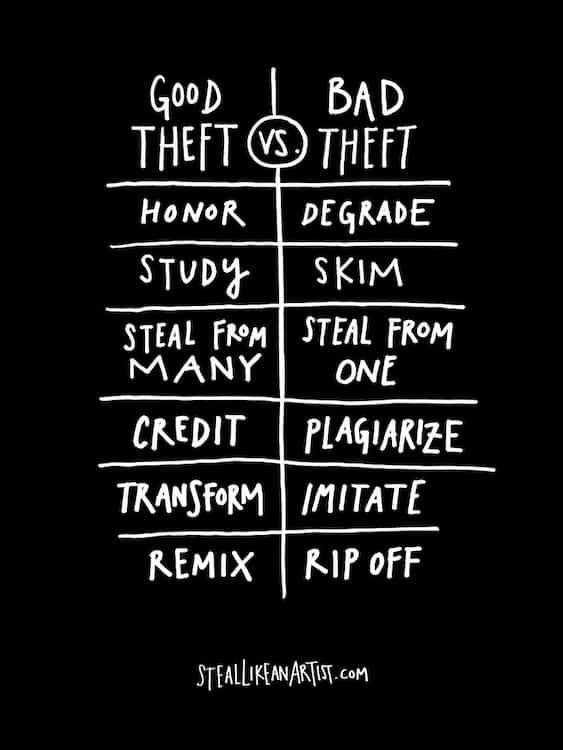

Austin Kleon, the author of the book appropriately called “Steal Like an Artist,” puts it even more clearly:

Start copying what you love. Copy copy copy copy. At the end of the copy you will find yourself.

Copywriters have an old-school technique where they copy by hand other copywriters to get their ideas as if they were their own. While you don’t have to handwrite your idol’s content, read their content while thinking about how they reached a given sentence, idea, or expression.

Go to an art museum, and you will see swarms of art students copying the masters. The same applies to iconic buildings with architecture students, dance students in ballets and dance competitions, etc.

As a writer, you must do the same—read your favorite writers, enjoy them, and take mental notes of the way they express themselves.

To close this writing technique, I want to share a final quote from the great William Zinsser (who I haven’t stopped quoting in this article):

Never hesitate to imitate another writer. Imitation is part of the creative process for anyone learning an art or a craft.

Find the best writers in the fields that interest you and read their work aloud. Get their voice and their taste into your ear—their attitude toward language. Don’t worry that by imitating them, you’ll lose your own voice and your own identity. Soon enough, you will shed those skins and become who you are supposed to become.

Study the writing masters, stand on their shoulders, and soon, you will write like them.

Stories draw people. The more stories your content has, the more engaged your readers will be.

Your stories, however, need to be short and concise; otherwise, you risk distracting your readers from the point of your article.

How do you create a story without taking forever to make your point?

By using the S.I.C. storytelling formula. Here’s how it works:

The S.I.C. writing technique is similar to the one about catchy intros (#6).

You create a problematic situation => you make it interesting by agitating the previous problem => you finish it with a solution.

Take the intro of this technique. The situation is that people like stories. But a story can become too long if you are not careful, so by using this writing technique, you can overcome that problem.

While it’s not a story per se, I use the same structure over and over.

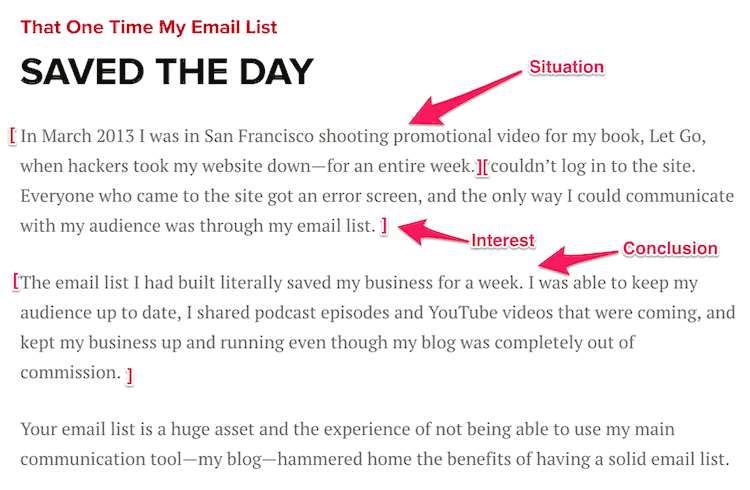

Take a look at what Pat Flynn does in this article about starting an email list.

If you were starting to learn about email list building, this story would be all you need to know about its importance.

Your stories don’t have to be as short as this one; you can add more details to it (remember to use sensory words), so the second part becomes increasingly more interesting.

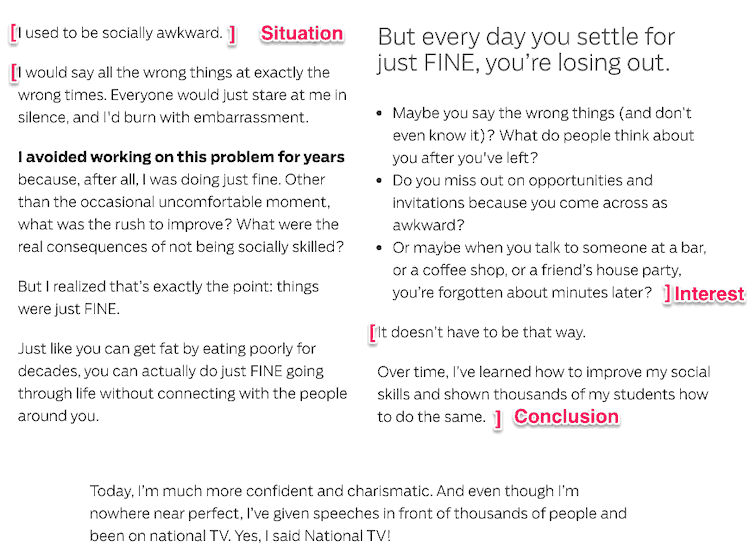

For example, take a look at what Ramit Sethi does in the intro to one of his evergreen guides:

While the conclusion isn’t as strong (he could have given more specifics about his and his student’s change), it’s still enough to get you hooked on the rest of the guide.

Avoid making the situation and conclusion too complicated and lengthy—all that matters is that your story is interesting.

In all of these examples, what makes the story unique is the person who was living it. Contrast the two previous examples with this article from GMB.

I love GMB, but their stories are too simple. How would I get elbow pain? How do you know having elbow pain is “excruciating”?

If the writer had told me a story he had about his elbow, it’d have been much more engaging. I’d have been able to imagine what that pain looked like.

You don’t have to base your stories on your life. You can invent stories by using words and expressions like:

The point is to use your reader’s imagination as much as possible, as often as you can.

To write stories on the fly, use your reader’s imagination as much as possible, as often as you can with some of the following expressions.

This writing technique goes hand in hand with the one about the senses—you want people to think, dream, and imagine themselves or someone they know living the situation you are explaining.

The more real and truthful the story, the more engaging it will be.

Most importantly, the more stories you can use, the better your writing will be.

You write, and write, and write some more. You are proud of the prose coming from the end of your fingers.

The problem is…your audience doesn’t care.

Whenever you write a sentence, paragraph, or idea, you need to think as if you were the reader and ask yourself: “so what?”

Here’s how this works:

Imagine you were writing an article about coffee brewing methods and you wrote a paragraph like this:

Anyone who knows anything about coffee knows what an espresso machine is – they’ve been keeping us caffeinated since 1901. Today they come in various shapes and sizes, with loads of features and gimmicks. Don’t get confused by flash machines though, because the basics are the same: pressurized water is pushed through a chamber (the puck) of finely ground coffee beans through a filter, resulting in what we call a shot of espresso.

Let’s ask, “so what?” for each sentence.

Sentence 1

Anyone who knows anything about coffee knows what an espresso machine is – they’ve been keeping us caffeinated since 1901.

“So what?”

It means espresso machines have been used for a long time, which explains its popularity.

Sentence 2

Today they come in various shapes and sizes, with loads of features and gimmicks.

“So what?”

It means there are multiple types of espresso machines with many features, some of which I will explain later. Still, it’s not clear what features and gimmicks I’m referring to, so it may not be relevant to mention them right now.

Sentence 3

Don’t get confused by flash machines though, because the basics are the same: pressurized water is pushed through a chamber (the puck) of finely ground coffee beans through a filter, resulting in what we call a shot of espresso.

“So what?”

It means they all work the same, regardless of the different shapes mentioned before.

Paragraph

The three sentences make sense on their own, but could they be explained in less space without cutting any ideas? It’s a possibility worth trying.

Let’s imagine you wanted to take the main ideas behind each of these three sentences and put them into one or two sentences.

This is how the paragraph could look like:

Baristas and coffee makers alike have been using espresso machines since 1901. Regardless of their shapes and sizes, they all work the same: pressurized water is pushed through a chamber/puck of finely ground coffee beans, through a filter, resulting in what we call a shot of espresso.

Does that look as good as before, but much more concisely? I believe it does.

Just like that, by asking yourself about the importance of the meaning behind each of your sentences, you’ve made a much more powerful paragraph while keeping its value.

Write for yourself (as you saw in technique #9), but when you edit your content, remember the reader (technique #10).

The reader doesn’t care about your opinions. He’s got many things going on; if your content doesn’t appeal to his interest, he won’t use it to understand your content.

Everything you write should have a purpose; it’s your job to find it and polish it.

Popular nonfiction writers, like Malcolm Gladwell and Steven Pinker, often write bestsellers thanks to their uncanny ability to write in such a way that almost everything makes a point. Every sentence and paragraph they put together push their idea or hypothesis forward, engaging you and delighting you in the process.

Your reader can forgive one or two irrelevant ideas. But if the answer to the “so what?” test constantly ends up with “it doesn’t matter,” then you’ll lose their attention and their respect.

You want your content to be pristine—clean and concise—something they can enjoy without having to worry whether you are going to tell them irrelevant, uninteresting information.

Next time you sit down to edit your content, ask yourself, “so what?” If the answer is “it doesn’t matter,” then you know what to do.

Pick one of the writing techniques and use it right away.

Which of the ten writing techniques from this post will you use in your content piece?

Come back and share your results. I can’t wait to hear what you do with it!

Notifications